Kill me right now. An essay by Simon Stone

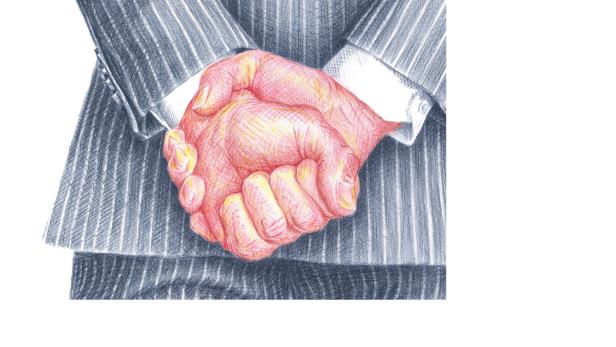

It was an early summer night on a terrace in the hills of Ibiza. We were staying at the holiday house of friends of ours. They had invited a selection of other acquaintances: a publisher, his wife and child; a prominent architect and his son. The setting and the company couldn’t have been more privileged. We’d been to the beach for a dinner of salt-crusted fish and multiple bottles of white. Then been driven home by the less drunk among us, along quiet country roads. The mood back at the finca was festive, tipsy, but also challenging – the kind of dick-measuring contest that inevitably takes place when four men, each at the top of their respective fields, compete for attention. It really couldn’t get more patriarchal. The wives, each more than significant in their own right, resigned themselves to witnessing the primordial jousting.

The friends whose finca we were at are hoteliers and their hotel is a kind of hotspot for the literati – actors, writers, artists, journalists all congregate there. Some of them to wind down; some of them to see and be seen. It’s what you imagine the fin-de-siecle salons were like. I myself came to be introduced to the place through actors I was working with at the Burgtheater nearly a decade ago. I was welcomed with open arms. It became my first home in Austria. And the kinds of discussions you had at that hotel really got to the heart of the cultural zeitgeist in Austria. The decision-makers, the movers and the shakers, they all sat over wine and cigarettes challenging each other on what mattered, what didn’t and why the fuck we’re doing what we’re doing. I felt lucky to have been invited in. My Australian imposter syndrome disappeared in an instant.

And so that night, over vermouth and tonic, we launched into one of those “important” conversations: the salon in exile on the Balearic Islands. The topic turned to political correctness. I should have run for the hills. I’ve never had a conversation in Central Europe about political correctness which didn’t end in either my interlocuter or I feeling great antipathy towards the other. And it had been such a pleasant evening so far. But certain elements insisted. And pushed forwards. I tried to retreat into rolling myself cigarettes and getting drunk. Tomorrow we’ll be gone, I thought. No need to engage.

And then it happened. The architect, who had been regaling us with his leftwing credentials (that kind of back-in-the-day you-can’t-imagine-how-radical-I-was monologue), placed his glass deliberately on the table and dropped the N-word. I looked at my wife. She blinked in disbelief. Maybe it was just a slip of the tongue, we communicated silently to each other. But no. He repeats it. Loudly and deliberately. And to the group, challengingly, he says “and I’m allowed to say that.” Silence. My wife looks around in astonishment, willing someone more confident in the group to say something. They don’t. I don’t even. Because I’m half in the bag and want to go to sleep.

For context, my wife is not the kind of person who picks fights. Nor is she the kind of person that can stomach any kind of discord. She’s polite to a fault. She lets people overtake her in queues to avoid conflict. She feels sheer panic speaking in public. So what happened next was awe-inspiring. The architect had just finished saying “I’m allowed to say that” and my wife looked around at the rest of the group, and finding them wanting, she said, quite simply, “No you’re not”. The architect stubbornly replied “Doch.” My wife dug her heels in, “No.” Nervous tension passed through the group, hoping the disagreement would resolve itself peacefully. It didn’t.

In an argument that I’ll spare you the ugly details of, we escalated rather quickly from robust political discussion to a bare-knuckled existential duel. After the architect had said something to the effect of “I’m not going to let a young woman tell me what my rights are” to my wife, my adrenalin kicked in and I gave up on going to bed early. My wife and I appealed to his better instincts: nothing doing. We tried to explain the perspective of those objectified and degraded by the N-word. All of this was irrelevant in the face of one fact that the architect held onto as justification of his right to freedom of racist speech: he had been one of the first architects in Germany to hire several Black assistants and interns in the 80s. He trained architects of African descent at a time when they were essentially sidelined or entirely ignored.

I’m sure there are African architects out there who feel they owe their careers to those opportunities. I’m sure there are Black German architects who wouldn’t have got a foothold had it not been for the chance to work with him. That pioneering work cannot be underestimated. But I’m also sure that had any of those protégés of his been around to hear him say the N-word they wouldn’t have said he’s entitled to it.

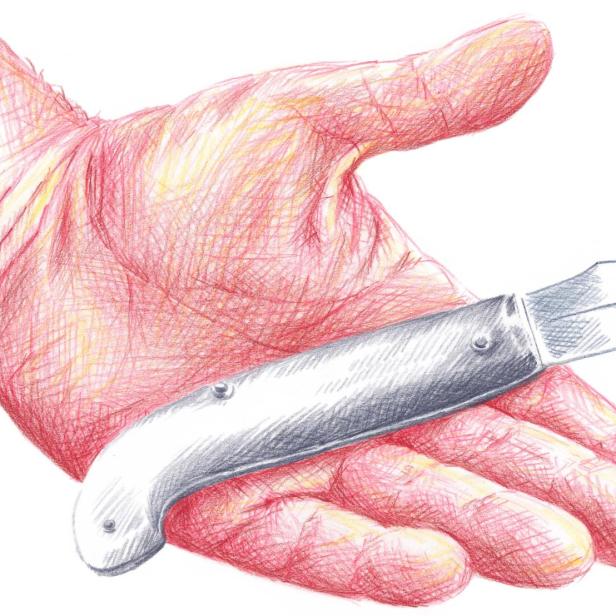

The evening came to an abrupt close when I proclaimed, “The world has moved on. Your sort will be gone soon,” and the architect pulled out a pocket knife and said, “Here then. Kill me right now.” At which I burst into fits of laughter. None of us, apart from my wife, came out of the disagreement in a particularly flattering light. There we were, a bunch of supposedly open-minded sophisticated liberals, discussing how we address (or don’t) centuries of oppression that we’ve benefited from. It was the very definition of a cultural echo chamber.

And this is the problem. Unless someone loses their mind to old age or insanity, we often don’t hear what the liberals are actually thinking. We assume, given the many examples of disproportionate representation, that the liberal patriarchy is probably racist and sexist. But we don’t have the proof because the (mostly) men in these positions are smart enough not to out themselves. But here we were, at the outing. And it essentially boiled down to the same old colonial logic: I helped the poor bastards, so I own them. I didn’t have to help them. Nobody else was doing it. I was the only one. They should thank their lucky stars that I even bothered. So if I want to call them a N***r then I’ve bought myself that right.

The problem with the 60s/70s generation of liberal is how easy it was to be radical. To travel the world funded by their parents, collect cultural artefacts from the remotest places and, after half a decade or so of smoking joints and growing their hair long, returning to their well-paid jobs and putting those artefacts on the walls of their expensive houses, reminders that they were once truly radical. They bought multiculturalism as if it was an item on a supermarket shelf. And yes, some of that generation did go so far as to start charities and exchange programs, hire minority employees, in the attempt to assimilate the disparate worlds of privilege and disadvantage. Which is why it was so terribly disheartening to hear that all this effort, in the case of the architect, was essentially to buy one right: to continue to call them N***rs.

Yes, it all stems out of a particular fear: the fear of dying out. The architect held a knife out to me and said “kill me now”. It may seem like theatrics, but I believe the gesture resonated in his soul. He saw a world he can no longer recognise and felt offended that it hadn’t made the effort to understand him, to integrate him into the future. As if growing old is meant to be easy. I wonder if he ever had a similar fight with his own father at some point in the past.

But unlike a generation of WW2 survivors, who looked at their children’s radicalism with disgust in the sixties and seventies, the current generation of ‘wise elders’ will not admit that they live in the past. They like to think that they re-invented the wheel and all revolution was done and perfected in their name. Further innovation is not only fruitless but offensive. At least our grandparents held stoically to their conservatism. They held it up as a well-worn principle. We knew where they stood. Our parents and their buddies are entirely convinced they’ve still got their finger on the pulse. And anyone that suggests otherwise is a charlatan.

But how exhausting this must be. To stay radical. In one’s own fantasy. Like Mick Jagger rattling his bones across a stage to a 60 year-old tune. A generation that feel they fought so hard to be heard, to be seen for the uniqueness of who they are. How unwilling to admit that that revolution was not the be-all and end-all of the cultural battle. That it was led by privileged white men and the few white women they allowed to join them. And that the true battle is only just beginning. Where people of as-yet-unrepresented backgrounds actually get to speak for themselves. And that the criteria for being listened to in the past (charming, gregarious, university-educated) were never built for equality.

We straight white men have had a rather easy road. I speak from experience. People listen when I open my mouth. I can lose my way and it’s the natural progress of a white artist’s journey. I got every opportunity that the opportunity-givers were so hungry to give a confident young white man. I fitted the prescribed image. And I cannot understand how any other straight white man can look at the history of the last three thousand years and not see the outsized imbalance of opportunity. And, no, providing a few exceptions only proves the rule.

Why wasn’t I the first one to speak up against the utterance of that hideous word that night? Yes I was drunk, yes I was overworked and tired, in no state to eloquently tear strips off a stubborn bigot. But all it required, as my wife displayed, was the simplest of “no”s. So why didn’t I say anything until my rather shy wife spoke up first? Because I found the guy charming. I found him impressive. I wanted to be in league with him. An artist’s life exists on connections and here was another potential ally, supporter. My wife and I were about to move to the city he and his wife were influential figures in. He drunkenly promised to pave our way. And part of me woke up the next up the morning dreading that I’d ruined that connection. That’s how the patriarchy works. It’s charming, inviting; it envelops you in feelings of your own self-worth. So long as you don’t question the fundamental bedrock of its existence. And how quickly the worm turns when you do.

Because the patriarchy has always been afraid. It has acted from its very inception as if it was in a state of perpetual near-annihilation. Untold religions and legal systems exercise ruthless control over women’s reproductive systems and by extension their bodies and their sexuality. And why? Because a woman with equal rights may just go ahead and reveal our fundamental impotence. Who other than an essentially impotent agent would need such perverse and imaginative ways of maintaining their hold on power?

Eine Bleistiftzeichnung eines Aschenbechers mit Zigarettenstummeln.

It seems – despite the horrific setbacks in certain parts of the world in terms of femicide and abortion control, and the ugly rise of more and more populist xenophobic governments – that in the internet age, minority voices have revealed themselves as what they are. Not minorities. Powerful collectives. People with agency. You’d think the generation of ’68 would be proud not threatened. Never before has there been grassroots activism that has such widespread impact. Maybe the only thing that’s annoying is that all of us, every now and then, will be revealed to have failings. About bloody time.

So to all the straight white men out there. There’s nothing to be afraid of. What’s the worst that can happen? That after millennia we finally become a minority voice? Maybe people will fetishise us like we have the minorities before us. At the very least we’ll finally have to prove our worth in the unforgiving marketplace of real opinions. And that might very well make better people of us all.

Illustration: Pascale Osterwalder